Jerry Lewis. Funniest man who ever lived, in my opinion, anyway. “The Nutty Professor?” I mean the original. Greatest film ever made. It still cracks me up. Forget about Eddie Murphy. Let’s talk about Professor Julius Kelp.

Today, in terms of showbiz icons who are still standing, Lewis is it, and he is still very much on view. At the age of 84, he spent a considerable amount onscreen hosting the “Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Telethon on Labor Day weekend. He still gets top billing over the illness and the kids he supports. God bless him. He deserves it.

He looked and sounded like an older Jerry Lewis, though at his age, he is certainly to be forgiven for not looking like a day older than he actually is.

In fact, this year, after a couple of seasons of severe illness that would have taken out weaker souls, he helped raise over 60 million dollars for Muscular Dystrophy, down over five million dollars than last year, but given the state of the economy, still a grand amount. And this without the participation, for the first time in years, of sidekick Ed MacMahon.

What was surprising, entertaining and inspiring, was that Lewis was on screen as much as he was. He no longer gets the cover of the Sunday newspaper insert, “Parade” magazine, nor does he – or the telethon – get the advance press it used to get, but the telecast still garners a huge audience. You don’t get over 60 million dollars in contributions otherwise.

Lewis, often sitting down this year, sang songs, bantered with the orchestra, and performed his famed, “Al Jolson Medley,” which he first introduced at the Palace Theater in New York City shortly after breaking up with his partner, Dean Martin. By the way, it was in that year–1957–when Lewis’ vocal recording of “Rockabye Your Baby (With a Dixie Melody)” became a surprise hit. Dean Martin was more surprised than anyone that year. Yes, there were plenty of on-air gaffes and screw-ups in this year’s telethon as always—centered on one of Jerry’s favorite subjects, Adolf Hitler, among other things—but that’s what happens every Labor Day weekend.

For the past several telethons and a camp highlight for me, Lewis has introduced a young, Buddy Love / Bobby Darin-type singer named “Michael Andrew,” who is supposedly being pegged to play the young Jerry in the Lewis-directed, Broadway production of “The Nutty Professsor.” Now, the show is supposedly set for 2011 and is said to have the participation of Marvin Hamlisch and Rupert Holmes. I’ll believe it when I see it. The Broadway version of “Professor” has been in the planning stages for five years now. “Michael Andrew will be a big star if he does what I tell him,” Lewis said on the telethon. I hope Michael Andrew will listen to Jerry Lewis.

Stranger things have happened.

Here’s one of them:

My first job after graduating Temple University was with a publication devoted to the film industry, called Film BULLETIN. The intent of this magazine, which had been published since the 1930s, was to help motion picture theater exhibitors choose the films they wanted to show.

Film BULLETIN was already an anachronism when I came aboard, but a job was a job and show biz was show biz. After roughly three years there, from about 1975 to 1978, I had built up some good contacts in the film industry, and I came up with what I thought were a couple of good ideas about what would fly in the film marketplace as well.

One of my more brilliant concepts was an idea for a screenplay. This would tell the fictionalized story of none other than Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.

I felt so strongly about it, I quit my job. I was out $125 per week.

Making a call to the story department of United Artists in New York where I had some connections, I spoke to a story editor. I introduced myself as being the Managing Editor of Film BULLETIN, and said, “I know you get thousands of phone calls like this, but I have an idea for a film.”

“Let’s hear it,” the woman on the phone said.

“Three words,” I said fearlessly. “Martin and Lewis.”

“Wow,” was the initial reply. “How soon can you have a screenplay on our desk?”

“Two weeks,” I said, thinking that sounded good.

The next call I made was to a high school colleague who graduated college with a degree in theater. I thought it would be a good move to contact someone who knew something about writing a play, which I didn’t.

His name was and is Eric Diamond. He had a wonderful sense of humor, a marvelous sense of theater and of music—remember that Martin and Lewis were as much about music as they were about comedy– and to me, seemed to be the perfect collaborator. We could bounce stuff off each other, and we would become big screenwriters.

Eric, by the way, has carved out a fabulous, 20-plus year career for himself in the theater department of Montclair State College in New Jersey. This guy knew, and knows, theater. He is currently the Chairperson of the Departments of Theater and Dance.

It also seemed to me that Eric, who had taken the plunge and the risk of moving to New York City right after graduating college, had the perfect locale—just off Broadway, as I recall—for two, fledgling screenwriters. This was as close as “let’s put on a show” as one could get circa 1978.

Though Diamond had a theater degree and I had worked as a magazine editor, the two of us had no idea as to the actual “form” that a movie screenplay should take.

We bought a book at a Manhattan book store. I think it was entitled “How to Write a Screenplay.”

I knew the story of Dean and Jerry pretty well from the book that Arthur Marx, Groucho’s kid, had written about them, and Eric Diamond had a good sense of the dramatic, what worked and what didn’t.

We had two weeks to write this thing.

We took individual turns writing sections of the script, which included entire musical sections of what was Martin and Lewis’ actual act at the 500 Club, the Copa, etc.

I was in heaven in New York, and why I didn’t stay, I still can’t say. During my first week in NYC, I grabbed the Times to see who was playing, jazz-wise in the area. Screenwriter or no screenwriter, I was and I am, first and foremost, a jazz drummer, and there was no way I could ignore where I was living, for the moment. On Broadway. I could see Howard Johnson’s when I looked out the window.

In the Times was a small ad for a tourist-type place called “Joe’s Pier 52,” that featured the piano “stylings” of the one and only Mary Napoleon and “his trio.”

Marty Napoleon? Jeez! He was the brother of longtime Gene Krupa pianist Teddy Napoleon (Teddy had passed in 1958), but more importantly, Marty had played with saxophonist Charlie Ventura. I had played with Charlie in Philadelphia several years before, so I had a connection. My goal? To sit in on drums, of course.

I think I schlepped Eric Diamond with me to Joe’s Pier 52. The next thing I knew, I introduced myself to Marty Napoleon and told him of my connection with Charlie Ventura. I was asked to sit in and I evidently, as they say, acquitted myself well.

I was asked to take the job playing drums, but I turned it down, telling Marty that I was occupied writing a screenplay.

Marty Napoleon, by the way, is still very much with us at the age of 88 and recently appeared as a part of the Harlem Jazz Museum’s lecture series in New York city.

Truth be told after all these years, I was scared to death to sever my ties with my hometown of Philadelphia and move to New York, screenplay or no screenplay.

The two week script deadline was approaching. Diamond and I put the finishing touches on our draft, which I think we called “Leave Them Laughing.” We used fictitious names for Martin and Lewis to dodge any possible legal action and registered the work with an organization called The Writer’s Guild of America/East. I don’t think either of us read the thing the whole way through.

I think Eric Diamond lent me a coat and tie for our impending meeting at United Artists in New York City.

We met with a woman who was an executive in the UA the story department. I’ll never forget it as long as I live. She asked us who we had in mind to play Martin and Lewis. I suggested Vic Damone and Charlie Callas. I remember distinctly that she said something about Al Pacino being under contract, and that she mentioned to us, “What if the Jerry Lewis part were played by a woman?”

I told her that the “dynamic” of our work would be changed, but that we were open to anything and that we would rewrite it if necessary. We could have it done in two weeks.

Several weeks later, back in Philadelphia, I received a call from United Artists, saying that they had passed on our screenplay.

I asked why.

“There is no conflict,” I was told. “A movie has to have a conflict that is somehow eventually resolved. Your script is just a straightforward telling, and a good one, of the story of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.”

“But the whole Martin and Lewis story was a conflict,” I replied.

“No one would really care today,” was the United Artists’ verdict.

On November 24, 2002, 24 years after our screenplay on the life of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis was submitted to United Artists, a television movie entitled “Martin and Lewis” aired on CBS Television. Sean Hayes, who starred on the television program “Will and Grace,” played Jerry Lewis. An English actor with a lot of B-movie credits, named Jeremy Northam, portrayed Dean Martin. A good deal of it was based on the Arthur Marx book that Eric Diamond and I used as our source material, and plenty of our shtick was in there. The project supposedly had the blessings of both the Lewis and Martin estates. The reviews of the show were lukewarm. They should have used Vic Damone. And Charlie Callas, too.

I remember trying to call Eric Diamond on the telephone the night the program aired. I couldn’t get through.

After seeing Lewis on television during this year’s telethon, and realizing that this may be one of the last times anyone might even see Jerry Lewis, I was moved to try to contact my collaborator again.

Though I’ve never been interested in reliving anything, perhaps I’m getting sentimental as I grow older. Or, quite simply, I just wanted to make contact with the talented young fellow who co-wrote the screenplay, “Leave Them Laughing,” that could have been made into a major motion picture by United Artists. Starring Al Pacino. And Charlie Callas.

This time, Eric Diamond answered the telephone, and we had a wonderful, long and heart warming conversation about Martin and Lewis and other matters. I think, as usual, I did most of the talking. Mainly about myself.

Eric will be visiting his family in Philadelphia within the coming weeks, and we have made plans to get together. I hope we do. Perhaps we’ll collaborate on something again.

This time, maybe it will be the story of The Ritz Brothers.

Starring Al Pacino.

So what is Jerry Lewis really like?

Let me tell you.

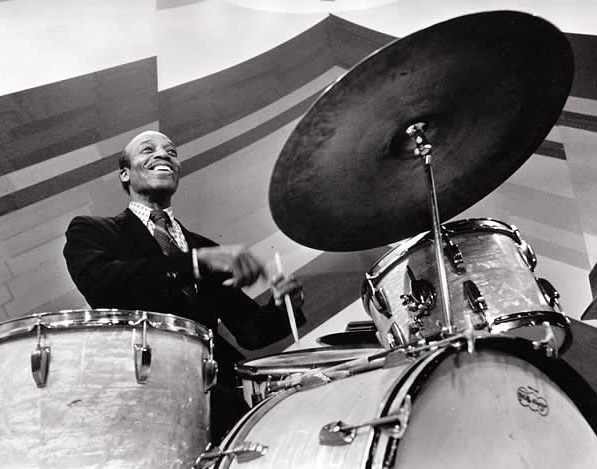

In 2001, I was in the midst of writing and co-producing a Hudson Music video production called “Classic Drum Solos and Drum Battles.” After being involved in a number of Hudson projects through the years–on Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich and various others–I became firmly convinced that the main reason folks bought these things was to hear the drum solos, and that everyone could live without the music portions leading up to it. “Classic Drum Solos and Drum Battles” would be just that. All drums and nothing but.

By the time we were set to go start putting this thing together, I realized I was about eight minutes shy of an hour, the bare, time minimum needed to release this thing to the marketplace.

I received a call, just in the nick of time, from a gentleman who then headed the international Buddy Rich fan club, Charles Braun.

“You won’t believe what I just found,” Charles breathlessly told me over the phone. It’s an eight-minute drum battle from 1955 between Jerry Lewis and Buddy Rich.”

I didn’t believe him. No one had ever heard of the existence of such a thing.

“Charles,” I said, “if this is true, then get it on my desk by tomorrow.”

He did, and it did exist. It was a segment from the television program, “The Colgate Comedy Hour,” which frequently played host to Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. The actual segment began as a comedy, featuring Jerry battling Buddy with a bunch of film tricks, various drums and dozens of pairs of sticks (Jerry was a good amateur drummer and the godfather of Buddy’s daughter, Cathy), but gave way to a fabulous, extended workout by Buddy Rich. In terms of time and material, it was just what “Classic Drum Solos and Drum Battles” needed.

I was wary of using it without permission, however. Jerry Lewis was still very much on the scene, and I was told that he kept a pretty close eye on how vintage film — with him in it — was used. I sent a letter to his Las Vegas offices, asking for permission to use the clip in our video, “for the good of jazz education and scholarship.”

Several weeks went by, and I heard nothing. Time was getting short. What was missing from this picture?

I sent the letter to Las Vegas again, this time with a check made out to the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Five days later, on a Saturday morning, the telephone rang at my home.

It was Jerry Lewis.

Forgive me for being star-struck, and I’ve known a lot of celebrities on a personal basis over the years, but it is not every day when Jerry Lewis calls your home.

Buddy Love himself. On the phone with me.

He was personable but very businesslike. I told him, before he even began, that not only was his call sincerely appreciated, but how much of an inspiration he had been to so many of us through the years. He thanked me and told me he knew of my work.

“I’m going to give you permission to use this film,” he told me, “and I’m going to send you a package next week of everything Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa did on the telethon over the years. Use it as you see fit. The only thing I ask is that I be remembered to Cathy and the family for this.”

I assured him that I would let Cathy and Marie Rich know.

“Classic Drum Solos and Drum Battles” was released by Hudson Music in 2001 and continues to do well, spawning two sequels in the process.

During my conversation with Jerry Lewis, there was no mention made of my screenplay, of Eric Diamond or of Al Pacino.

But Jerry Lewis called my house. I hope he will again. Maybe during next year’s telethon.