The death of Oscar Peterson is a major blow to the jazz world. Like Buddy Rich, OP was so professionally and personally powerful that you got the sense he would always be around.

Like others who have received the rarity of popular success in this business — think Dave Brubeck, Ramsey Lewis, Maynard Fergusion, Eddie Harris, Louis Armstrong and many more– Peterson got more than his share of criticism in the press. For his time, he was likely second only to Art Tatum in terms of technique, and negative comments usually had to do with his over-abundance of chops. The critics said the same thing about Buddy Rich, so the important factors in jazz, according to the scribes are: Don’t be too popular and don’t have too much technique. And, darn it, don’t swing too much.

The various Oscar Peterson trios were legendary and super-charged, and no one could out-swing them. Many of learned the vocabulary of jazz from Oscar, Ray Brown and Herb Ellis, and many of us learned taste from the drumming of Ed Thigpen. It has been said more than once that, if there is anything close to a “perfect” piano/bass/drums recording, it would have to be the Oscar Peterson Trio’s version of “West Side Story.” There were more classics as well, including the original “Very Tall” with Milt Jackson and the exquisite solo sides he made for the BASF/Saba labels in Europe.

The late Norman Granz, who brought Peterson to the United States from Canada and served as his personal manager from the early 1950s, loved the man and his playing and just could not record enough of him on his Clef, Norgran and Verve labels in the 1950s and early 1960s, and on his Pablo label in the 1970s and 1980s. There were those who also said Peterson was over-recorded. Bet they’re not saying it now.

There were jazz pianists and there were jazz pianists, and perhaps some of them had Oscar’s technique, most notably the late and troubled Phineas Newborn, Jr. But they were not Oscar Peterson.

****

While we’re on the subject of the jazz press, it is important to remember that there are three monthly publications devoted to covering jazz in this country. They are, of course, Jazz Times, Down Beat, and a rather under-rated publication called Jazziz. My brother, the musicologist Joel Klauber, along with yours truly, were regular contributors to Jazziz when the publication was relatively new (it is now close to 25 years old, I believe). Like the others, Jazziz has its areas of specialization, mainly in the area of what is known as “smooth jazz.” Maybe Jazziz has not been taken seriously enough because smooth jazz has not been taken seriously enough. No matter. Things are changing, and the early results are impressive. New Executive Editor Fernando Gonzalez has a great piece devoted to Nat Cole in the December issue, and I urge all of you to check it out, and/or visit them on the web at Jazziz.com. I have recently contacted my old colleague there, founder/editor/publisher Michael Fagien, about returning to the Jazziz fold as columnist. Stay tuned.

****

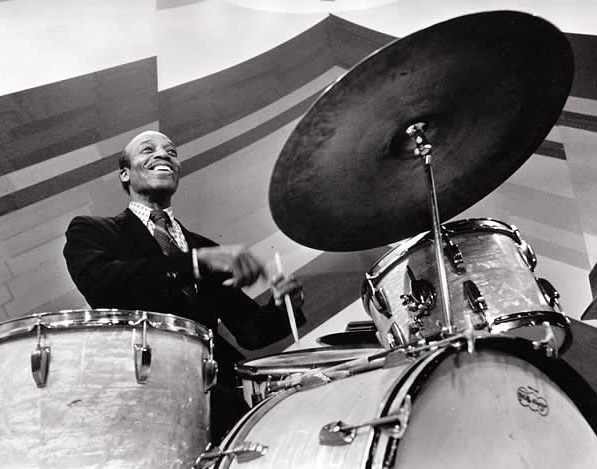

Super-drummer Steve Smith has just finished work on another Hudson Music DVD, entitled “Steve Smith’s Jazz Legacy.” That’s also the name of Steve’s band, which is an outgrowth of his Buddy Rich tribute group, “Buddy’s Buddies.” The Legacy grouping gives Smith and his band the flexibility to highlight compositions by other great drummers, and songs that great drummers made famous. This upcoming Hudson release features the Jazz Legacy in performance, paying tribute to artists like Max Roach, Joe Dukes, Elvin Jones, Art Blakey and Philly Joe Jones, breaking down the elements of their drumming technique, explaining his own philosophy about just how he is paying tribute to these percussive giants, and much, much more. I cannot say enough about this project, or about Steve Smith. As a drummer and as a tireless and incisive educator, there is no better. Currently in release and just as essential is Hudson’s “The Art of Playing Brushes,” presented by Steve and Adam Nussbaum and featuring Charli Persip, Joe Morello, Eddie Locke, Billy Hart and Ben Riley. This project represents essential viewing for anyone who ever picked up a pair of brushes…or wanted to. The amount of work that goes into these productions is absolutely staggering, and believe me, I know. What is so wonderful about these titles is that the “work,” if you want to call it that, is evident on the screen. Both projects, by the way, have plenty of clips and photos of the vintage variety, including newly-discovered film of Philly Joe Jones. My good friends Rob Wallis, Paul Siegel and editor Phil Fallo deserve all the kudos all of us can muster for these titles. For more information, visit HudsonMusic.com.

****

For reasons of time and scheduling, I have had to drop out of consulting for the proposed Gene Krupa “Broadway” show and possible band tour. Watch this space for updates, which will be printed as we get them from Arthor Von Blomberg and his very talented group of associates. As previously mentioned, if anyone can get something like this off the ground, it would be Arthor.

****

We are getting some great, great comments and feedback on the new design of the JazzLegends.com site. Keep the comments and suggestions coming in, and watch for more web site evolution.

****

Writer Burt Korall, author of the definitive books on drummers of the swing and bop era and good friend of Gene, Buddy and many others, passed away not too long ago. On a topic detailed here previously, Korall was among several writers and critics who, for whatever reason, refused to acknowledge my work and my existence. To this day, I have never figured this out. Believe me, I am not in this business–if this is a business at all–for credit, money or good reviews. I only continue to try to contribute something to jazz scholarship and education. But for a guy like Korall to go out of his way to NOT include any mention of the existence of “Gene Krupa: Jazz Legend,” “Buddy Rich: Jazz Legend,” “Legends of Jazz Drumming,” etc., in books that COVERED these things, was and is an absolute disgrace. That’s why there are supposed to be editors, but the editors missed the boat on this as well. I often wonder what someone like Korall got — or John McDonough gets — out of behavior like this. Is it jealousy? A sense of power? The jazz community is small enough as it is for us to be criticizing or panning or ignoring our fellow artists. Saxophonist Sam Butera, long-time leader of Louis Prima’s back-up group, The Witnesses, used to end his own shows with the following: “Remember,” he would say to the audience, it’s nice to be important, but it’s more important to be nice.”

Corny? Maybe, but how about resolving to live that, and live up to it, for the year 2008 and beyond.

Bruce Klauber, January, 2008.